Posts Tagged Frederick Douglass Jr.

Virtual Presentation -> Lost History of Frederick Douglass, Simon Wolf and Jewish Washington [May 1 & May 29, 2023]

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on February 27, 2023

Diary tells of evening of tea & music at Rochester home of Frederick Douglass family in March 1861 on the eve of the Civil War [Never before published full account from diary of Julia Ann Wilbur, friend of Dr. Douglass from Rochester to Washington City]

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on May 1, 2018

Julia Ann Wilbur was a friend of Frederick Douglass for decades from Rochester to Washington City.

Women in the World of Frederick Douglass published last year by Oxford University Press has done much to advance an understanding of the consequential and expansive networks Dr. Frederick Douglass ran with, largely overlooked in existing scholarship.

Prof. Leigh Fought’s work is one of the most substantive and important books to join the canon of Douglassoniana Studies since Dickson Preston’s groundbreaking Young Frederick Douglass in the early 1980s.

Douglass’ associations and relationships with women propelled his life and elevated his worldly education from the first recollections of his widely-respected grandmother Betsy Bailey to the last conversation he ever had with his second wife Helen Pitts.

While Prof. Fought’s work places many women in the Douglass network, in documenting the collaborative working relationships and associations in the liberation struggle from the abolitionist movement to suffragist movement there are, of course, many more women to be uplifted in the pages of our fallen history.

Last fall, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time: Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose, was published by Potomac Books, an important addition to the periphery family of Douglassoniana Studies.

The work by journalist and historian Paula Tarnapol Whitacre brings to attention an important and forgotten friend of Dr. Frederick Douglass.

According to the publisher:

In the fall of 1862 Julia Wilbur left her family’s farm near Rochester, New York, and boarded a train to Washington DC. As an ardent abolitionist, the forty-seven-year-old Wilbur left a sad but stable life, headed toward the chaos of the Civil War, and spent most of the next several years in Alexandria devising ways to aid recently escaped slaves and hospitalized Union soldiers. A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time shapes Wilbur’s diaries and other primary sources into a historical narrative sending the reader back 150 years to understand a woman who was alternately brave, self-pitying, foresighted, petty—and all too human.

Wilbur’s diary makes numerous mentions of Douglass, including March 1861 evening at the Douglass family home

Throughout Whitacre’s work there are several references to Douglass. The author alludes to the development of Wilbur’s friendship with Douglass from attending lectures to visiting Douglass in his Rochester home for an evening spent with his family listening to music and having tea.

A Civil Life cites Wilbur’s diary as the source for the anecdotal visit to the Douglass home but the full text has never been published before nor included in existing Douglass biography and scholarship. (Please correct me if in error.)

We thank the municipal government of Alexandria, Virginia for making this incredible resource available to scholars and in the same radical spirit of ladies who ran with Dr. Douglass the militant scholarship — never before published material slowly putting together the millions upon millions of pieces of the puzzle — continues like chatterboxes holding the thrown seat on the all-night 70 bus.

——

This P.M. Mrs. Coleman went with me to Frederick Douglass’ & we took tea with all his family & spent the evening. It was a very pleasant & interesting visit. Mrs. Watkyes & Mrs. Blackhall & Gerty C. were there.

There was sensible and lively conversation & music. Mrs. D. although an uneducated

black woman appeared as well, & did the part of hostess as efficiently as the generality of white women.The daughter Rosa is as pleasant & well informed & well behaved as girls in

general who have only ordinary advantages of education. The sons Lewis, Freddy, & Charles, aged 21, 19 & 17 respectively, are uncommonly dignified & gentlemanly young men.They are sober & industrious & are engaged in the grocery business. F. Douglass is away from home much of the time engaged in lecturing. He continues a Monthly Paper & of course it takes a part of his time. It will be one year tomorrow since his little daughter Annie died under such painful circumstances, & they all feel her loss very much.

Apprehensions for her father’s safety, & grief for his absence caused her death. She was a promising child. She was 11 years of age.

SOURCE:

Diary of Julia Ann Wilbur. Rochester. March. Teusday[sic]. 12th. 1861

Julia Wilbur Papers, Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections.

h/t Douglassonian Candace Jackson Gray

Frederick Douglass, Jr. letter to Simon Wolf & Simon Wolf letter to Frederick Douglass, Jr. (National Republican, 22 May, 1869)

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on March 18, 2018

THE QUESTION OF COLOR.

THE QUESTION OF COLOR.

INTERESTING CORRESPONDENCE.

Application for a Clerkship from Frederick Douglass, jr.

Yesterday Simon Wolf, esq., the newly appointed register of deeds, received the following letter from Frederick Douglass, jr., a brother of Mr. Douglass, at the Government office, (and not the “colored printer at the Government office,” as erroneously stated in the Star of yesterday.) The letter will be read with interest at this time:

Washington, D.C., May 21, 1869.

Simon Wolf, esq., Register of Deeds:

DEAR SIR: I have the honor to request an appointment as clerk in the office of which you have the distinguished honor to be the head. I belong to that despised class which has not been known in the field of applicants for position under the Government heretofore. I served my country during the war, under the colors of Massachusetts, my own native State, and am the son of a man (Frederick Douglass) who was once held in a bondage protected by the laws of this nation; a nation, the perpetuity of which, with many others of my race, I struggled to maintain. I am by trade a printer, but in consequence of combinations entered into by printers’ unions throughout the country, I am unable to obtain employment at it. I therefore hope that you will give this, my application, the most favorable consideration.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, JR.

To this letter Register Wolf made the following reply:

To this letter Register Wolf made the following reply:

RECORDER’S OFFICE

Washington, D.C., May 21, 1869.

Your application is before me, and has received favorable consideration. I see no reason in the world why you or your race should not have the full countenance in the struggle for progress and education, and I am particularly happy in being the means of encouraging you; for, as a descendant of a race equally maligned and prejudged, I have a feeling of common cause; and who can foresee but what the stone the builders reject may become the head stone of our political and social structure.

Very respectfully,

S. Wolf

—

SOURCE:

“The Question of Color,” 22 May, 1869. The National Republican, 1.

LECTURE: Our Bondage and Our Freedom: Frederick Douglass and Family in the Walter O. Evans Collection (1818-2018) [Annapolis, Feb. 23, 2:00pm – 3:00pm]

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on January 22, 2018

While there have been many Frederick Douglasses – Douglass the abolitionist, Douglass the statesman, Douglass the autobiographer, Douglass the orator, Douglass the reformer, Douglass the essayist, and Douglass the politician – as we commemorate his two-hundred anniversary in 2018, it is now time begin to trace the many lives of Douglass as a family man.

Working with the inspirational Frederick Douglass family materials held in the Walter O. Evans Collection, this talk will trace the activism, artistry and authorship of Frederick Douglass not in isolation but alongside the sufferings and struggles for survival of his daughters and sons: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Remond and Annie Douglass.

As activists, educators, campaigners, civil rights protesters, newspaper editors, orators, essayists, and historians in their own right, Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Remond and Annie Douglass each played a vital role in the freedom struggles of their father. They were no less afraid to sacrifice everything they had as they each fought for Black civic, cultural, political, and social liberties by every means necessary. No isolated endeavor undertaken by an exemplary icon, the fight for freedom was a family business to which all the Douglasses dedicated their lives as their rallying cry lives on to inspire today’s activism: “Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!”

Guest speaker: Dr. Celeste-Marie Bernier

Celeste-Marie Bernier is Professor of Black Studies and Personal Chair of English Literature at the University of Edinbourgh and she is Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of American Studies published by Cambridge University Press. Dr. Bernier is an esteemed international scholar, having won many notable awards. In 2010. she was the recipient of a Philip Leverhulme Prize in Art History while in 2011 she was awarded an Arts and Humanities Research Council Fellowship. In 2012 she was given a Terra Foundation for American Art Program Grant for an international symposium on African Diasporic art which was held at the University of Oxford. In 2010, she was awarded a University of Nottingham Lord Dearing Award for “Outstanding Contribution to the Development of Teaching and Learning.”

In addition to supervising large numbers of PhDs and MRes to completion, she has held visiting appointments and fellowships at Harvard, Yale, Oxford, King’s College London and the University of California, Santa Barbara, in addition to her recent position as the Dorothy K. Hohenberg Chair in Art History at the University of Memphis (2014-15) and her appointment (2016-17) as the John Hope Franklin Fellow at the National Center for the Humanities in Durham, North Carolina.

Dr. Bernier is a world renowned Frederick Douglass scholar and prominent author. In 2015, she published Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American. For the bicentenary of Frederick Douglass’s birth in 2018, she is preparing a new scholarly edition of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave in addition to numerous other publications and activities that will include an exhibition as well as international symposia and public workshops. In 2018, she has numerous forthcoming books about Douglass’s life including, “Struggles for Liberty:” Frederick Douglass’s Family in Letters, Writings, and Photographs; Living Parchments: Artistry and Authorship in the Life and Works of Frederick Douglass; If I Survive: Frederick Douglass and Family in the Walter O. Evans Collection; and “I am the Painter:” Imaging and Imagining Frederick Douglass.

Date and Time: Friday, February 23, 2:00pm – 3:00pm

Location: Legislative Services Building, Joint Hearing Room, 90 State Circle, Annapolis, Maryland

Please note: a valid photo ID is required to enter the Legislative Services building.

Event sponsor: The Honorable Delegate Cheryl D. Glenn

Program is presented by the Maryland State Archives.

[Editor’s Note: In September 2014 we attended a lecture by Dr. Celeste-Marie Bernier in the Annapolis State House on the exhaustive research she and Prof. Zoe Trodd conducted in archives throughout the United States and world tracking down photographs of Douglass.]

Masthead of “The Leader” includes Associate Editor Frederick Douglass, Jr. [8 December, 1888]

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on October 31, 2014

Frederick Douglass hosts Liberian officials in Uniontown [Evening Star, 25 June 1880]

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on July 17, 2013

In the late 19th century, while Frederick Douglass lived in Anacostia, scores of notable men and women came to Cedar Hill. In conversation Monday with Mr. Donet D. Graves, Esq. about his ancestor James Wormley, I learned of a dinner Douglass held hosting officials from Liberia.

For Douglassonian scholars this should be of some intrigue because Douglass was forceful in his denunciation of “colonization” efforts throughout his life. Without getting too much into the specific history of Liberia or “colonization” efforts both nationally and in the District, I only learned a couple years ago that there was such a concentration of black Marylanders in Liberia that there was a republic named “Maryland” in Liberia. Maps of Africa from the late 18th century – early 19th century regularly reflect this. Today there is a county in Liberia named Maryland.

Without further delay, here’s the brief news item.

MARSHALL DOUGLASS entertained at dinner at his residence, at Uniontown, yesterday afternoon. Dr. E. W. Blyden, minister of Liberia to England, and Hon. John H. Smythe, U.S. minister resident to Liberia, at which dinner were also present Senator Bruce, Prof. Greener, L. H. Douglass, Robert Parker, James Wormley, Fred. Douglass, jr., and Charles Douglass.

SOURCE:

Evening Star. 25 June 1880, p. 1 Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

Thank you to Donet D. Graves, Esq., a gentleman and scholar, for this helpful lead.

Incorporation Certificates filed for “The New National Era and Citizens Publishing Company” [New National Era, April 17, 1873]

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on September 3, 2012

Messrs. Lewis H. Douglass, James Storum, and Richard T. Greener yesterday filed in the office of the Recorder of Deeds a certification of incorporation of “The New National Era and Citizen’s Publishing Company,” the capital stock of which is fixed at $20,000, with the following trustees: L. H. Douglass, R. W. Tompkins, George D. Johnson, R. T. Greener, John H. Cook, Charles R. Douglass, and Frederick Douglass, Jr. – Daily Morning Chronicle.

Arson attempt on the offices of Frederick Douglass’ The New Era? [Baltimore Sun, May 1871]

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on June 17, 2012

On Thursday January 13, 1870 The New Era made its appearance in Washington, DC with the backing of Frederick Douglass, a newspaperman lest we forget.

The paper’s name was derived from the abolitionist newspaper The National Era which was published weekly in Washington from 1847 to 1860 under the editorship of Gamaliel Bailey and John Greenleaf Whittier. From 1851 to 1852 it published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in serial form. During the Pearl Affair, the largest planned escape of slaves in American history, in 1848 a mob almost destroyed their offices.

Plans to start up a “colored paper” in Washington, DC were in the works in the immediate years after the Civil War with folks like George T. Downing urging Frederick Douglass to take a leading role. Douglass, after running three previous papers, has been described as the reluctant editor. This is true.

A couple days after The New Era paper appeared on the city’s streets, the Baltimore Sun‘s “Washington Letter” ran a paragraph acknowledging the launch of the “colored people’s paper.”

“The New Era made its appearance this morning. As heretofore state, it is to be the organ of the colored people of the country. The editor is Rev. Sella Martin; corresponding editor Frederick Douglass. The first issue contains a card from Douglas, stating that pressure of his business prevented him from sending an editorial this week. Three white and one colored printer perform the work of composition.” [The colored printer being Fred, Jr.]

By the end of the year the paper had problems. Promises were made to Frederick Douglass that were apparently not kept and Douglass ended up going all in, anteing up his hard-earned dollars to ensure the paper’s survival.

In February 1871 the District of Columbia Organic Act become law, consolidating the governments of the city, Georgetown, and Washington County. As a Republican man in what was then a Republican city, Douglass was considered a leading candidate for the position of non-voting Delegate. Douglass wasn’t sitting on his hands.

Before moving to Washington Douglass was widely known on both sides of the Atlantic for his outspokenness on the page and lecture stage. However influential in political and literacy circles, not everyone agreed with Douglass’ advocacy and the positions his paper, The New Era / New National Era took in demanding equal rights under the law for freedmen and women. Douglass, a man who came up in the streets of 1830s Jacksonian Baltimore but came of age in Rochester, New York, would often remind folks, “Washington was an old slave city.”

That said, I find Douglass involvement with the New Era/New National Era/New National Era-Citizen another overlooked dynamic of his time in Washington, DC. Foner, Quarles, and Deidrich give it a fair shake. McFeely’s gross negligence and slothful treatment of the paper is downright blasphemous. (About a decade ago there was a panel at the DC Historical Studies Conference on Douglass and his DC paper but at the time I was still a teenager on my own come up so I missed it. I have been unsuccessful in contacting one of the panel’s participants to find out what was said and presented.)

In all the treatments of Douglass and his DC paper in books, academic journals, and other published material looking backwards I’ve never come across what looks to be an arson attempt on the paper’s offices.

In all the treatments of Douglass and his DC paper in books, academic journals, and other published material looking backwards I’ve never come across what looks to be an arson attempt on the paper’s offices.

In late May 1871 this item shows up in our trusted Baltimore Sun “Washington Letter” column…

“About noon to-day the printers in the office of the New Era newspaper, on Eleventh street, near Pennsylvania avenue, saw smoke coming up through the floor from the pawnbrokership of Issac and Lehrman Abrahams, on the floor below. The police were at one notified, and broke open the doors, when the discovered a large pile of rags and other light material piled up on the floor and burning. The material has been previously saturated with kerosene. The fire was extinguished, and as the two Abrahams were seen to leave the shop a few minutes previously, they were at once arrested on the charge of arson.”

Whew. OK. What does this say? Were the Abrahams trying to arson their own business to collect insurance, trying to burn down the offices of the New Era, or just crazy pyromaniacs?

A quick review of my own files of the the May 25th, June 1, and June 8th editions of the New Era didn’t reveal any mention of this failed arson attempt. But that doesn’t mean it’s not there and I overlooked it. I will do another review soon and will see what I can find in the Evening Star from May 1871 down at the Washingtoniana Division.

All in all, this might be not be nefarious but as they say where there’s smoke there’s fire.

To be continued…

Death knocked on the door of the Frederick Douglass family too often, Douglass outlives his wife, two children, and numerous grand-children

Posted by jmullerwashingtonsyndicate in Uncategorized on June 14, 2012

Death knocked at the door of the family of Frederick Douglass all too frequently. When a parent buries a child the natural evolutionary order of life is upset. Frederick Douglass buried two of his children. Just nine of Douglass’ twenty-one grandchildren lived to adulthood.

Death knocked at the door of the family of Frederick Douglass all too frequently. When a parent buries a child the natural evolutionary order of life is upset. Frederick Douglass buried two of his children. Just nine of Douglass’ twenty-one grandchildren lived to adulthood.

When his youngest daughter Annie died in March 1860, less than two weeks short of her 11th birthday, Douglass was in Glasgow, Scotland, having fled the country after he was implicated in John Brown’s failed raid of the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry in November 1859.

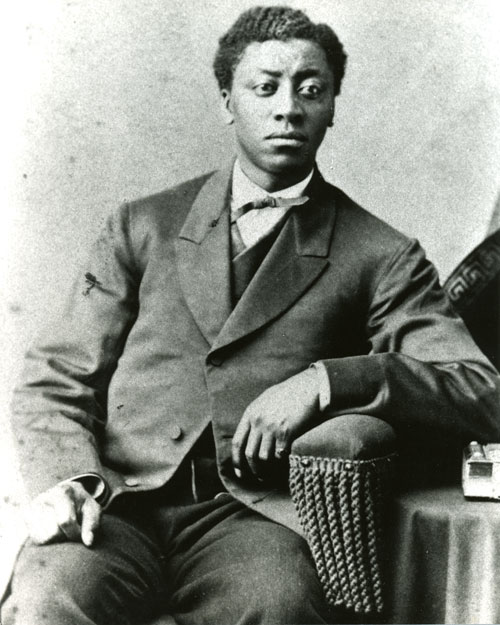

Anna Murray Douglass passed away on August 4, 1882 and nearly ten years later, as a heat wave swept through the city, on July 26, 1892 Douglass’ middle son and namesake, Frederick, Jr. died. He was fifty years old.

From the National Tribune, 4 August, 1892.

Tuesday, July 26. – Frederick Douglass, jr., a son of the noted colored man of that name died at Hillsdale, a Washington suburb, today. Mr. Douglass was for some time employed in the office of Recorder of Deeds in the District of Columbia, having gone there while his father was the Recorder, but for the past five years has been a clerk in the Pension Bureau.

And from the Washington Post, 5 November, 1887.

Death in Fred. Douglass’s Family

Charles R. Douglass, son of Frederick Douglass, is at present sadly afflicted in the loss of his two elder children, Chas. F. and Julia A. Douglass, of typhoid fever. The disease was first taken by the son about five weeks ago and by the daughter about two weeks ago, since which time the three other children have been attacked and one of them is now lying at the point of death. Charles was about twenty years of age and the daughter about fifteen. The son’s death took place Wednesday night and the daughter’s the following night. The two bodies will be interred at Greenwood this afternoon.